The Rise of the Golden Oyster in Michigan – What Foragers Need to Know

/Hello Mushroom Hunters!

My name is Andrew, and this is my very first blog post for Michigan Mushroom Hunters. I wanted to kick things off with a species that’s been all over the news lately — the Golden Oyster mushroom and its supposed "invasion" of the Midwest.

As mushroom foragers in Michigan, we know the truth is more complicated.

My First Encounter

I started hunting mushrooms in West Michigan, around the Grand Rapids area — long before I earned my state certification in wild mushroom identification through MAMI. Like many beginners, I made plenty of misidentifications early on, but I always turned to certified experts for clarification.

I’ll never forget one early Sunday morning in late summer. The air was crisp, fog hung low over the trail, and I rounded a bend to a bright splash of yellow on a massive oak tree. Golden Oyster mushrooms — unmistakable in color — were growing in several beautiful clusters along the trunk and roots.

I harvested a small cluster to identify later and left the rest. After some research, consultation with online ID groups, and cross-referencing with sites like MushroomExpert.com, I confirmed it: Golden Oyster (Pleurotus citrinopileatus). This was back in 2017.

So… Are Golden Oysters Really a Problem?

Observations of golden oysters in Michigan have steadily increased over the years, and it's important we understand why. In this post, we’ll focus on three key factors that may be contributing to their spread.

Golden Oyster observations in Michigan, 2020 (inaturalist.com)

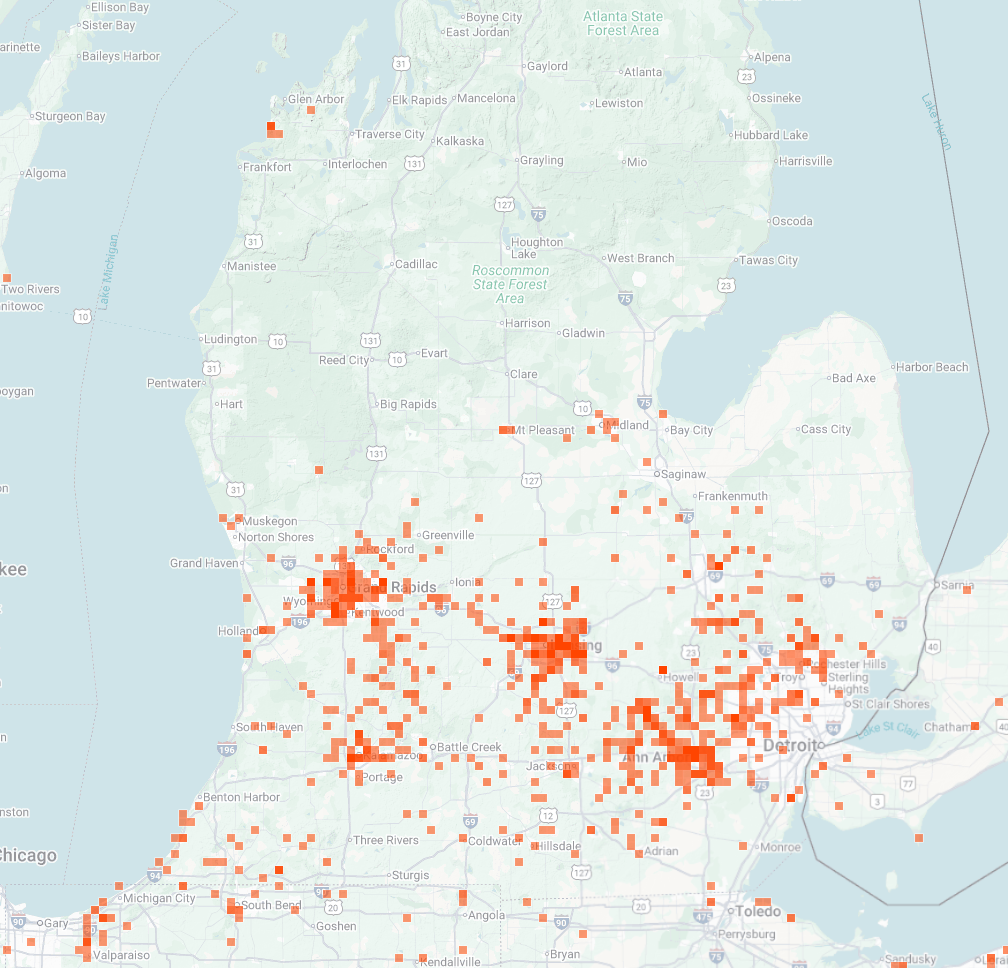

Golden Oyster observations in Michigan, 2024 (inaturalist.com)

Species Snapshot: Golden Oyster Mushroom

Pleurotus citrinopileatus

Bright yellow when young, fading to pale tan as they age

Decurrent gills that run down the stipe

Fruits primarily in late spring and early fall

Both saprophytic and parasitic, meaning they can decompose dead wood and infect living trees

Native to eastern Asia, now found worldwide

Spores spread easily via wind, water, and animals

Because they are non-native, our local trees — particularly oaks — may lack resistance. Local insects don’t feed on them, which may allow golden oysters to spread unchecked, potentially outcompeting native fungi over time. In a warming climate, this becomes an even bigger concern.

Three Reasons We’re Seeing More Golden Oysters

1. More Observers Than Ever

Access to technology and platforms like iNaturalist has exploded. In 2020, Michigan had 244,048 observations logged by 13,204 observers on iNaturalist. By 2024, that jumped to 473,889 observations from 17,850 observers. More eyes = more reports.

2. Foraging Is Booming

Interest in mushroom foraging has grown thanks to Google trends, social media, celebrity mycologists, and educational groups like ours. This means more people are noticing fungi that previously went unnoticed.

3. Commercial Mushroom Farming

Michigan now has more medium and large mushroom farms than ever before. Golden oysters are popular with growers and sold as fresh mushrooms or grow kits. These farms ventilate humid grow tents — and unfortunately, that often means spores are released into the air and environment.

Some growers are taking responsibility. Mycophile’s Garden in Grand Rapids, for example, has decided 2024 will be their last year producing golden oysters after reviewing the data. On the other hand, North Spore, a national supplier whose products we’ve used in library workshops, currently has no plans to stop distributing golden oyster cultures in the Midwest.

Climate Change is worth mentioning

Golden oysters fruit well between 70–85°F, warmer than many of our native Pleurotus species, which prefer cooler temps. With rising temperatures due to climate change, the golden oyster will only become more common.

What Can We Do?

Remove golden oysters when found in the wild (carry them in an open plastic bag)

Do not buy from growers who sell golden oyster grow bags or spawn in Michigan

Use iNaturalist to document sightings

Support native species by growing and eating local Pleurotus varieties

Final Thoughts

Right now, it’s hard to say definitively that golden oysters are displacing native fungi — but the potential is there. I first found them parasitizing a lone oak tree back in 2017. Years later, that same tree was cut down by parks services. I can’t say for sure why…but I have a suspicion.

We may only see the true impact 5–10 years from now.

Let’s stay informed, stay curious, and stay responsible as stewards of Michigan’s wild spaces.

Sources:

Inaturalist observation chart over time https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?subview=map&taxon_id=504060

Foraging google trends from the last 5 years https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&geo=US&q=foraging,Golden%20Oyster&hl=en

DNR warnings

Mushroom of the Upper Mid-west - Marrone and Yerich

© 2014 “Golden oyster are new to our woodlands, growing gregariously, likely invasively on dead or dying deciduous trees”

Mushroomexpert.com entry - Kuo https://www.mushroomexpert.com/pleurotus_citrinopileatus.html

“Pleurotus citrinopileatus is apparently an example of a species that has "escaped" from cultivation and has begun to naturalize itself in eastern North America. It represents a cultivated, yellow "oyster mushroom" whose natural origins are unclear (although it was first described in eastern Asia and may originate there).”