Essential Tools & Resources for Mushroom Foragers

/Maybe you’ve just joined us for our open group hunt in late August. Maybe you’re stepping into your own backyard to check out mushrooms for the first time. Or maybe you’ve been living deep in the woods, sneaking online with a Starlink connection.

Wherever you are on your mushroom journey, these are the tools and resources I personally use almost every day. Because I respect your time, this blog focuses on three areas:

Online resources like MushroomExpert.com

Foraging gear that keeps you safe and effective

Field guides worth carrying into the woods

“Coral tooth fungus” Hericium coralloides found by an attendee at our August Open Group Hunt

Fit Check for Our Mushroom Era

Before we even talk about books or websites, let’s start with the basics: protect yourself first.

When you’re out in the woods, the biggest risks aren’t just from wild mushrooms — they’re from mosquitoes, ticks, and the environment itself. The easiest way to reduce those risks is with protective clothing and insect repellent.

Yes, this means the glorious comeback of mosquito head nets. They may not win style awards, but together we can bring them back into fashion.

Now, insect repellent is always a hot topic among foragers and conservationists. As visitors to wild spaces, we have a responsibility to leave no trace — which includes being mindful of the chemicals we spray around. Personally, I try to avoid DEET and other heavy chemicals whenever possible. But I’ll be honest: in deep mosquito country, I sometimes cave.

If you’re looking for an alternative, I recommend trying Grandpa Gus’s products. They’re a solid option for keeping ticks and bugs at bay without leaving as much chemical footprint behind.

Identification Resources

My first mushroom guide? Checked out from the library…and, shamefully, never returned. (Don’t worry, years later I donated money to make up for it.)

Since then, I’ve built a personal collection, but the one I use at every hunt is Mushrooms of the Upper Midwest: A Simple Guide to Common Mushrooms by Teresa Marrone and Kathy Yerich. It’s compact, affordable, and incredibly well organized — perfect for beginners and intermediate foragers. Until I write my own Michigan guide, this is the book I use to teach others.

Online Tools

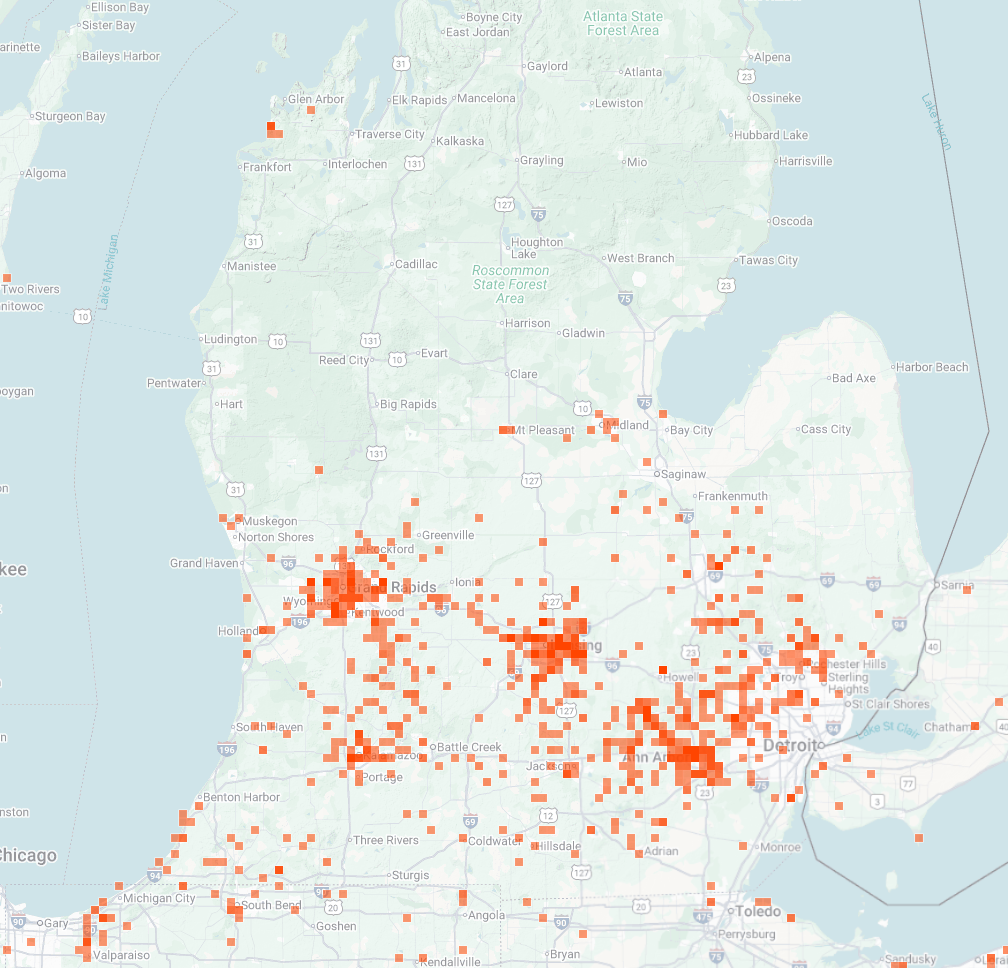

Academics used to side-eye online resources, but let’s be honest: they’re indispensable now. My go-to is MushroomExpert.com, run by Michael Kuo. I use it constantly, especially when helping others identify fungi from around the state.

That said, beware of misinformation. AI-generated content is on the rise, and not all websites are trustworthy. Never, ever eat a mushroom just because a website says it’s safe. Only you are responsible for what goes into your body.

Apps & Citizen Science

Apps like Seek by iNaturalist are excellent for documenting fungi and contributing to scientific data. I use them during group hunts to demonstrate how easy it is to record local biodiversity. Still — just like websites — don’t rely on them for edibility decisions.

Community ID Help

When you’re stuck, sometimes a second opinion helps. I’ve had success using ID groups on Facebook and Reddit. Experts can often point you in the right direction with just a few photos and details.

But be careful: not everyone online has your best interest in mind. Use responses as guidance, not final answers, and always confirm IDs through multiple sources.

Lastly, Michigan’s state certification program maintains a list of certified mushroom identifiers each year. Check to see if there’s an expert in your county — they’re an invaluable resource.

Gear Up!

The tools you bring into the woods matter more than you might think.

Bags: Plastic bags are a no-go. They trap heat and moisture, causing mushrooms to rot quickly. Use paper or cloth bags instead. My top pick? A potato sack or forager’s basket. Bonus: paper bags allow spores to disperse as you walk. (Plastic bags get a pass only if you’re carefully removing invasive Golden Oysters.)

Knives: A simple pocket knife works, but if you want to upgrade, try Opinel’s mushroom knives. I also treasure a hawk-bill folding knife from Old Timer — gifted to me by a fellow forager on a guided hunt.

Advanced Tools: If you’re ready to level up, consider a UV flashlight to check for reactivity and a small set of test chemicals like ammonia. These are especially useful for tricky genera like boletes. You can pick up supplies from HomeScienceTools.com.

I hope this guide helps you prepare for a rewarding fall mushroom season. If you’d like to put these tools into practice, join us on an open group mushroom hunt this October or November — the last ones for 2025!

Come walk with us, talk fungi, and explore Michigan’s wild spaces.

Thanks for reading — now gear up and get out there, hunter. These mushrooms won’t find themselves.